Inversion of Control in Unity

Many developers come to Unity from a background in object-oriented programming and look to use the same patterns in Unity that they used elsewhere. You don't neglect what you have learnt elsewhere just because you are using a different tool but sometimes you have to apply those lessons differently with the new tool. Unity has its own idea about how you should architect a game and before you start fighting against this it is best to try working with it - you will be a lot more productive if you do.

Everything is a MonoBehaviour

The first principle of working with Unity's architecture is that everything should be a MonoBehaviour. Which means everything should be a component on a game object. Even the stuff that doesn't represent a feature of a specific game object, like code that initialises the scene or code that saves the current game state - just create an empty game object, call it something sensible like "scene controller" or "services" and add these components there.

If your code is a MonoBehaviour then Unity knows about it, the Unity editor knows about it, and the tools that Unity provides will work with it. If your code is not a MonoBehaviour then it sits outside of Unity's knowledge and ability to manage it and you can't configure it in the Unity editor.

(Scriptable Object is an exception to this but you probably don't need that.)

The editor

There is one disadvantage to making everything a MonoBehaviour - you have to work with two IDEs. The first is your coding tool - usually MonoDevelop or Visual Studio - and the second is the Unity editor. You can't spend your day entirely inside your coding tool of choice, you have to mess with the Unity editor as well. But that's okay. You create the components in your code editor and you configure them in the Unity editor, just like you would any other asset.

Inversion of Control

All of which is an introduction to my real reason for writing this article - a lot of developers new to Unity struggle with inversion of control, or more precisely the apparent lack of it. You may come from any programming background, but if you are used to having a dependency injection container or service locators you may well regard Unity as inferior and you may even decide to create a dependency injection container for it. Before you do, take a look at what Unity does out of the box.

In common use inversion of control falls into three categories -

- Service locators

- Dependency injection

- Events

Unity has tools for all of these. Some of them may not look like the tools you are accustomed to but they have much the same goals and produce similar results.

Service locators

Unity's service locator is the Find… methods of the Object class - FindObjectOfType and FindObjectsOfType. These methods will find the components in the current scene that match a particular type, and if you followed my advice above then all of your code is inside components of some object or objects in the scene. So if, for example, you have a component called "ScoreService" that submits scores to your server, just call FindObjectOfType<ScoreService>() to locate it.

Some developers complain that the find methods are slow, but

- They will rarely impact the performance of your game

- If they do impact performance, use dependency injection instead

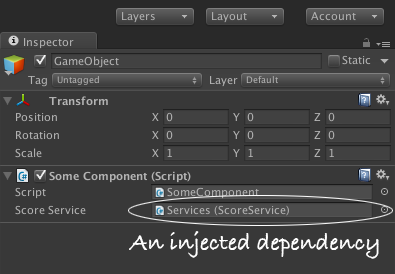

Dependency injection

You know that thing in the Unity editor where you drag one game object onto a property of another to provide the component instance for that property. That's dependency injection. It may feel a bit strange configuring it in the editor, but it's a lot easier to understand than the pages of code or XML used to configure most dependency injection containers.

Unfortunately configuring dependencies in the Unity editor is so easy you won't feel as smart as you did when you used Spring or Robotlegs - even your designers can configure this dependency injection.

Events

There's three ways to handle callbacks into an object.

1. SendMessage

Unity has had the SendMessage method since the dawn of time. It works but is less than ideal because it requires matching a string in the caller to a method name in the callee, which requires setting global rules about the naming of methods (or losing any benefit of SendMessage over just calling the method directly).

2. Actions

If you code in C#, you get Actions for free as part of the language. Actions are delegates that don't return a value and as such are great for event dispatching. Unfortunately, the Unity editor doesn't understand them so they have to be configured in code, but that's what you thought you wanted anyway isn't it.

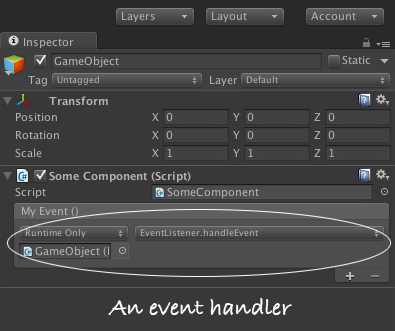

3. Events

Since the introduction of Unity's new GUI in version 4.6 Unity includes an event system that can be configured in the editor - so if a game object dispatches an event you can configure the listeners for that event inside the editor rather than in code. It feels odd at first, but if you embrace the idea of building your components in a code editor and configuring them in the Unity editor then, as with the dependency injection, this will make absolute sense. Try it.

Conclusion

Unity has it's own tools for managing inversion of control. They are unlike the tools in most web frameworks but they do the same job and in some cases they are even easier to use.

The first game I wrote in Unity was a struggle as we broke all of the above rules to code the game the way we did with other tools. With my second and subsequent games I follow the Unity patterns and I build games faster and have more fun doing it.

Also in the collection Unity Game Engine